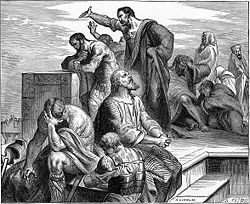

Babies with their brains dashed against stones (Psalms 137)

We've taken some hits for this card, which puts us in good company: so has God. We and the Almighty would like some vindication.

We (the creators of the game, not God) went to different "Christian liberal arts colleges" where we heard too many people, including religion professors who should have known better, accuse God of "dashing babies against rocks" with omnipotently calloused hands, or ordering the children of Israel to do so, using this passage as a source.

Does the Divine Warrior occasionally order the slaughter of whole nations, men, women and children, in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament? Yes (see our post about "Not giving a $h!t about the Canaanites"); however, this psalm is not such an example, and it is important to recognize that.

The speaker is not God, it is an individual crying out to God on behalf of his (some scholars argue her) people in their time of abject suffering. They are "by the rivers of Babylon," mocked by their oppressors after their Temple has been destroyed, their mothers and daughters raped, their fathers and sons decimated, and the survivors death-marched across a desert.

This is a song of lament hummed traversing The Middle Passage, chanted across the Trail of Tears, whispered in cattle cars to Auschwitz.

From a heart of sorrow the psalmist wishes equal harm to befall his/her tormentors, cries to the heavens for it to be a reality, but God does not swing any infants by the ankles, nor order such to take place. God's hands are clean and so is the singer's. No Babylonian children were harmed in the making of this psalm. But that is (almost) a secondary point.

Here is what should give you pause:

If you cannot fathom the level of anguish required for a normal person to wish a gruesome death upon another's child, then you have lived a charmed life and should praise whatever deity you hold dear; but how dare you blithely minimize or judge someone else's expression of a pain you can't comprehend?

Who are we to criminalize another, not for action, but a plea of distress to God? And what hubris does it require to indict God for not condemning them for their poetic, emotional release?

Perhaps we should ease up on people in pain.

Perhaps we should allow them to honestly grieve in their own way.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we're going to Hell anyway.

![O Come, O Come Emmanuel (Isaiah 7:14) [An Advent Card Talk]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55a9a1e3e4b069b20edab1b0/1483161046976-X5VJE3CMP9T957O72EII/3d-wallpapers-light-dark-wallpaper-35822.jpg)