There are 66 books in the (Protestant) Bible, but only about eight in the Good Christian's Choice Selections of Common Praise for Worship, Remembrance, and Joy Together in Song Book of the Faith . . .

Wet Dreams (Deuteronomy 23:10)

Covenant Cut by Cupping Crotch (Genesis 24:2-9)

Have you ever wondered if there is a connection between the words “testicles” and “testify”? No? Then you will live longer because you haven’t seen this linguistic fight raging on the internet between lay people and academics alike; not only whether there is an etymological link between the two words, but if that supposed linkage extends to legal practice.

With variations, the story holds that Roman soldiers and/or citizens would swear civic oaths while holding their own manhood, or the manhood of the person they were swearing the oath to. The idea being that the testes were a witness to virility, and/or the general idea, if I’m lying, you can cut these off! (we leave it to you to use Google effectively and lose yourself in the penile debate). But why in the world is A Game for Good Christians writing about this? If you take the Google challenge offered above you’ll notice that quite a few of the relevant sites refer to or quote the passage on this card.

In Genesis 24:2-9, Abraham orders his most trusted servant to find a wife for his son Isaac; however, Abraham wanted this unnamed servant to “swear by the Lord, the God of heaven and earth, that you will not get a wife for my son from the daughters of the Canaanites” (vs. 3). To swear this oath, Abraham told his servant to “put your hand under my thigh” (vs. 2). Joseph repeats a similar ceremony in Genesis 47:28-31. So is there a connection at all between these Biblical events and our modern day, English words?

While there is linguistic Latin tie between “testes” and “testify— as testis means “witness”— neither are Hebrew words used in the text. Thus it is interesting the number of people who cite the Biblical story as proof of the convention. We wonder if the argument is that the practice continued until the Romans gained control of Judea, saw the actions of their enslaved people, and said, “oh, yeah. Grabbing the other guy’s balls! They must be serious! Let’s do that!” This says nothing of the fact that the historical debate rages on as to whether or not this was indeed a Roman custom. However, regardless of the Roman context this is exactly what is happening in the Bible.

Many translations render the English as “put his hand under the thigh.” The Hebrew root for the word “thigh” is yarek, which can be translated as the upper portion of the thigh, but use your imagination: picture someone facing a male, placing his hand under the inner portion of his upper thigh. Where would his hand be?

The word also referring to genitals in passages like Genesis 46:26 and Exodus 1:5, though it is sanitized by translations that focus on presenting a simplified meaning of the passage over the literal Hebrew. Many insert the phrase “the descendants” or “the direct descendants” to identify the offspring of the patriarchs mentioned, truncating the text. Non-fancy versions like the KJV preserve the literal Hebrew:

All the souls that came with Jacob into Egypt, which came out of his loins (yarek), besides Jacob's sons' wives, all the souls were threescore and six (Genesis 46:26, KJV)

And all the souls that came out of the loins (yarek), of Jacob were seventy souls: for Joseph was in Egypt already (Exodus 1:5, KJV)

Perhaps it’s time to find an old new statement for court room proceedings:

Do you swear to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing by the truth?

Grab my crotch and hope to die, I do!

But what do we know? We made this game and you probably think we’re going to Hell.

You were so misunderstood . . .

If We Read One More Ignorant Thing About The Bible . . . [A Rant]

Note: This is a revision of something We posted on our old blog over two years ago. We felt it was time to dust it off. Strap in.

Notice the above graphic/website and its title. Click. Surf around. Spend some time on it and then come back.

Ready?

Let us first say, we love this on many levels. It’s smart, it’s creative, it’s colorful, it’s providing a good service. We just wish it wasn’t so wrong. So damned-by-God wrong. All over the place. Wrong.

Beyond understandable ignorance, things that most people don’t learn and have no reason to learn outside of a serious Bible study, seminary, or a level of theological/biblical neridty boarding on psychosis (welcome to our world), there are other things that are just dumb: things a thinking person would question as being odd in the presentation.

But to be clear we are talking to and about Christians reading this, as much, if not more so than the creators of the site. We fear most Bible reading Christians make the EXACT SAME mistakes when interacting with the Bible that the creators of all this interactive awesomeness. In some ways we respect the Skeptics more than the Christians as a result. They have an excuse.

Below we outline a handful of these mistakes made by both groups— Bible skeptics and Christians we want to kick— in the hopes that someone, somewhere, will stop making them. These are arranged by category but in no real order.

Chronology matters

- We shouldn’t even have to say this. The books in the Bible weren’t all written at the same time, by the same human hand, regardless of what you think about Divine Inspiration. The order you read things in makes a difference. (Example: stop complaining about how people in Genesis broke the 10 Commandments when the 10 Commandments didn’t exist yet.)

Words have meaning

(“You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means”)

- Just because an English word is used in the Bible doesn’t mean that the Hebrew (or Aramaic) in the Hebrew Bible, or the Greek in the New Testament mean the same thing at all. At all. AT ALL.

- Just because you read a word in English doesn’t mean it’s the same word in Hebrew/Greek every time it appears in that verse. Apply this to different chapters, books, sections, Testaments. [Repeat.] (Example: In Exodus, when talking about the “hardening” of Pharaoh’s heart, three (3) different Hebrew words are used for “hardened” throughout the narrative. The specific words, their order, and the surrounding context matters.)

Reading comprehension

- Just because it is in the Bible doesn’t mean that the Bible condones the action/idea. Saying something happened is not the same as saying people should do it. (Example: the Bible mentions suicide by hanging, sacrificing children to foreign gods, and pulling out of one’s sister-in-law during sex.)

- Just because an idea/action/situation/entity appears (in translation) in the Bible, does not mean that what is true in the 21st century was exactly how that things operated in the iron age of the Ancient Near East. (Example: “slavery” in Israel was nowhere even remotely the same as African slavery in the antebellum American South. Not one damn bit)

- Just because you are able to read one verse doesn’t mean much. Read the verse in context. Context includes the surrounding verses, the chapter, the section of the book, the whole book, the section of the Bible/type of literature. (Example: A psalm is not the same as a geneology; The Deuteronomistic History is not the same as the Gospels; The P-source is different than a pseudo-Pauline text. If you said, “what?” to any of those you’ve proved our point.)

Inner-Biblical Interpretation

- (This one sends us to Hell) Just because it says something in the New Testament, that doesn’t mean that the writers of the Hebrew Bible would have agreed with it. [What?] The New Testament contains specific commentary of the fledgling “Jesus movement,” who were either Jews trying to figure out their relationship with Judaism (“Are we a new sect or a new religion?”), or gentiles who were switching from some other religion. The writers of the NT are interpreting the Hebrew Bible: the writers of the Hebrew Bible wouldn’t agree with everything the NT writers said, and the NT writers don’t always agree with each other on specific passages (Example: Paul in Romans 4 and James in James 2 on Abraham’s binding of Isaac). Furthermore, you could disagree with the interpretation of a NT writer (Example: contra Hebrews 12, Esau wasn’t “immoral and godless,” he just made a stupid decision).

Some General Rules of Thumb

- Stop accepting what you learned in Sunday School as truth, especially if you haven’t actually read the passage you’re talking about in years, or ever.

- Stop thinking Moses, Jesus, and Paul spoke your version of idiomatic English.

- Stop trying to harmonize the Hebrew Bible with the New Testament on all issues: They are two collections of books, not two single texts to Venn Diagram.

- Stop trying to harmonize the Gospels: they don’t all say the same thing, and that’s on purpose.

- Stop trying to make the Bible a scientific textbook.

- Stop trying to make the Bible into your social justice textbook.

- Stop trying to make the Bible into your personal therapist.

- Stop trying to make the Bible into anything other than the Bible.

- Stop imposing your monochromatic picture of God on reality and then getting pissed off when the Bible disagrees with that overexposed nonsense. You did that. Not the Bible. Not God.

Again, there are examples on this site that do not have a simple, Google/Wikipedia/think-damnit answer, which scholars and people of faith have wrestled with for centuries. But honestly, the vast majority of the things on this page are not that difficult to deal with when the things above are considered.

Which brings us to our real point:

If as much time was spent researching the answers to these “contradictions” as was spent putting this awesome visual together, while we doubt anyone would be converted, the level of cynicism would ratchet down a notch, and a begrudging respect for the Bible might emerge.

But what do we know: we made this game, which you probably think is worse than the Skeptic’s website, thus we’re all going to Hell.

God Causing All of Your Problems (Psalm 88)

"Seriously God, what the f . . . ?"

~ Too many hearts from the beginning till now.

Here is the harsh reality: over 80% of the psalms contain some measure of complaint or request for assistance from God. Well over 1/3 of the Psalter are psalms of lament, what Walter Brueggemann calls psalms of disorientation. These are the psalms that record the loss of stability, the loss of equilibrium from our lives. Conflict and trouble have crept or charged in. The world is not as it should be. We are clawing at the sides of a dark pit, while our ever-present enemies taunt our pain like a dangled rope.

In much of modern western Christianity, psalms of lament are disrespected. If not completely ignored, they are made into songs, included in sermons, and thrown into bad Christian self-help books by cutting out the cries of pain and focusing on the possible happy endings. Pain is only seen as a path to progress. Hurt paves the road to heaven.

Troubling words and images are revised or culled altogether, and calls for vengeance have little place in polite churches. There is no asking YHWH to destroy enemies like salt does a snail, or to make those who harm us like a stillborn fetus (Psalm 58). It is inappropriate to bestow heavenly blessings upon those who smash the oppressor’s babies against jagged rocks (Psalm 137). None of that fits polite church culture. That level of pain is censored.

Similarly, Psalm 88 is forgotten – so forgotten it is not even included in the Revised Common Lectionary. Why? Because Psalm 88 doesn’t play nice with the other psalms: She’s the rebel who said to hell with biblical poetic conventions, I do what I want.

There is a structure that all psalms of lament follow. They contain 1) an address to God, 2) the raising of complaints and/or petitions to God, 3) a confession of trust in God, and finally 4) a promise to praise God once He comes through. In some respects, psalms of lament are how some issue fox-hole prayers: “God, shit just got real. I need Your help. Even though the situation looks bleak, I know You got my back. Thank You in advance. I owe You one.”

All psalms of lament follow this basis structure. All of them contain a petitioned problem but end in pronounced praise. All of them. Except Psalm 88. It is the only psalm without a turn toward hope, praise, or promises to God.

More than that Psalm 88 is an indictment of God: The Lord sits not on His throne but on the witness stand.

O Lord, God of my salvation,

when, at night, I cry out in your presence,

let my prayer come before you;

incline your ear to my cry.

For my soul is full of troubles,

and my life draws near to Sheol.

I am counted among those who go down to the Pit;

I am like those who have no help,

like those forsaken among the dead,

like the slain that lie in the grave,

like those whom you remember no more,

for they are cut off from your hand.

In the sleepless night, we cry, we beg for God to hear our prayer, but hear no answer. Our soul full of troubles, our life on the brink of death, we feel forgotten by silent skies and lead-covered clouds. The only thing we are sure of is the source of our pain, the one who stands accused:

You have put me in the depths of the Pit

in the regions dark and deep.

Your wrath lies heavy upon me,

and you overwhelm me with all your waves.

You have caused my companions to shun me;

you have made me a thing of horror to them.

I am shut in so that I cannot escape;

my eye grows dim through sorrow…

From the witness stand, the divine is silent. The Almighty seems to plead the fifth. But still we press the witness for answers:

But I, O Lord, cry out to you;

in the morning my prayer comes before you.

O Lord, why do you cast me off?

Why do you hide your face from me?

Still no answer is forthcoming, only a realization:

Wretched and close to death from my youth up,

I suffer your terrors; I am desperate.

Your wrath has swept over me;

your dread assaults destroy me.

They surround me like a flood all day long;

from all sides they close in on me.

You have caused friend and neighbor to shun me;

my companions are in darkness.

And there the psalm ends. There is no turn towards the good. There is no easy resolution or a nod toward the possibility of one. It ends emotional, evoking the words of a grief-stricken C.S. Lewis: “The conclusion I dread is not 'So there's no God after all,' but 'So this is what God's really like. Deceive yourself no longer.’” ~ A Grief Observed

What do we do with this? First remember our humanity, and the humanity of the author.

“The Psalms, with a few exceptions, are not the voice of God addressing us. They are rather the voice of our own common humanity – gathered over a long period of time, but a voice that continues to have amazing authenticity and contemporaneity. It speaks about life the way it really is, for in those deeply human dimensions the same issues and possibilities persist. And so when we turn to the Psalms it means we enter into the midst of that voice of humanity and decide to take our stand with that voice. We are prepared to speak among them and with them and for them, to express our solidarity with the anguished, joyous human pilgrimage. We add a voice to the common elation, shared grief, and communal rage that bests us all.” ~ Walter Bruggemann, Praying the Psalms

Second, we remember the reality of our perception. Sometimes God is hidden from our sight, silent to our ears, beyond our grasping, bloodied fingers. And that is why this psalm is so beautiful and appropriate to complete the Psalter.

It is present to say the questions “why?” and “how long?” are appropriate. That asking “what did I/he/she/we/they do to deserve this?” is valid.

That it is okay to scream, even at God, because the lines of communication are still open: at least you’re still talking.

And besides, God can take it.

But what do we know? We made this game and you probably think we’re going to Hell.

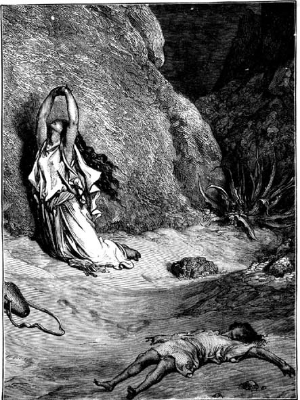

"Hagar in the Wilderness," Gustave Dore

If the above didn't drive you to drink, then you should read about why “There really aren’t enough good hymns written about_______”

Babies with their brains dashed against stones (Psalms 137)

We've taken some hits for this card, which puts us in good company: so has God. We and the Almighty would like some vindication.

We (the creators of the game, not God) went to different "Christian liberal arts colleges" where we heard too many people, including religion professors who should have known better, accuse God of "dashing babies against rocks" with omnipotently calloused hands, or ordering the children of Israel to do so, using this passage as a source.

Does the Divine Warrior occasionally order the slaughter of whole nations, men, women and children, in the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament? Yes (see our post about "Not giving a $h!t about the Canaanites"); however, this psalm is not such an example, and it is important to recognize that.

The speaker is not God, it is an individual crying out to God on behalf of his (some scholars argue her) people in their time of abject suffering. They are "by the rivers of Babylon," mocked by their oppressors after their Temple has been destroyed, their mothers and daughters raped, their fathers and sons decimated, and the survivors death-marched across a desert.

This is a song of lament hummed traversing The Middle Passage, chanted across the Trail of Tears, whispered in cattle cars to Auschwitz.

From a heart of sorrow the psalmist wishes equal harm to befall his/her tormentors, cries to the heavens for it to be a reality, but God does not swing any infants by the ankles, nor order such to take place. God's hands are clean and so is the singer's. No Babylonian children were harmed in the making of this psalm. But that is (almost) a secondary point.

Here is what should give you pause:

If you cannot fathom the level of anguish required for a normal person to wish a gruesome death upon another's child, then you have lived a charmed life and should praise whatever deity you hold dear; but how dare you blithely minimize or judge someone else's expression of a pain you can't comprehend?

Who are we to criminalize another, not for action, but a plea of distress to God? And what hubris does it require to indict God for not condemning them for their poetic, emotional release?

Perhaps we should ease up on people in pain.

Perhaps we should allow them to honestly grieve in their own way.

But what do we know: we made this game and you probably think we're going to Hell anyway.

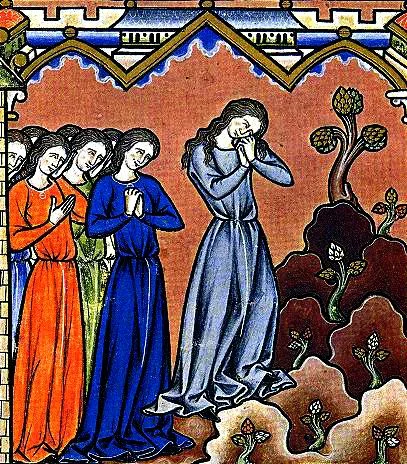

Jephthah's Daughter (Judges 11)

God regretting your existence (Genesis 6:6)

Here is a not funny question: is this card about you?

Like the story of the people in the Flood Narrative (Noah and the Ark, lots of rain, bloated dead bodies everywhere once the rain subsides), do you, have you, or could you bring YHWH to a place of feeling like this when thinking of you? [NSFW-sort of]

We think it's an important question. Not just globally, not as a nation, but individually.

Personally.

Perhaps good, modern, progressive, liberal, open and affirming, beloved community, non-offensive, rosy-colored-glasses Christians, have strayed from the Biblical (and common sense) idea that there is only so much crap God will put up with from each of us.

Perhaps we need to stop thinking that the notion "God is love" means that God doesn't care about our personal acts of evil in the world. That God simply pats on us the head, gently chiding us to do better, and wrings Divine hands at the predicament He is unable to get a grasp on.

Perhaps we should remember that the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament both contain the idea that God is in possession of the full range of emotional options; that God can get pissed off fairly quickly when people are mistreating others.

Perhaps we should keep in mind that "divine wrath" is predicated on "divine love" — an idea Good Christians have no problem remembering when talking about caring for the abstract poor, widows, and orphans, but seem to completely forget when the conversation turns to their own brands of personal evil/sin.

Perhaps personal floods sweep through our lives from time to time for just this reason. Let's just keep hoping that we're Noah in the story.

But what do we know: we made this game, so you probably think we'll be the first to descend to a watery Hell

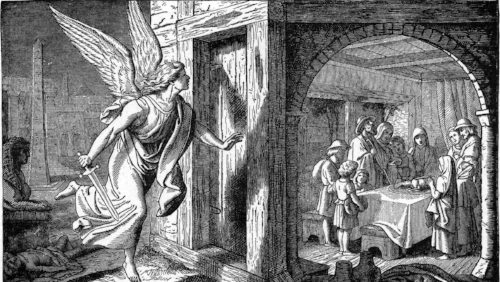

Pissing Powdered Golden Calf (Exodus 32:20)

Playing the whore with many lovers on top of every high hill and under every green tree (Jeremiah 2:20)

We had a long post planned for this one: a carefully articulated, poetically worded, Scripture laden treatise to prove a central point; but allow us state it crassly, boldly: Take your complaints about patriarchal language and shove them for a moment and realize that God loves you, loves us, love the Jews of Jeremiah's day, and was hurt by their actions against Him, our actions again Him, your actions. Mine.

Jeremiah paints God as a hurt lover, like Hosea, Isaiah, and Ezekiel did before him. That is the heart of the text.

Have you ever been cheated on? Have you had someone you cared for rip your heart out, when all you ever did was love them as best you could? Have you ever asked them "why" and got a shrug in return? Have you desired to take them back when you know the outcome will leave you in tears again?

There were so many things we were going to say, rephrasing, rehashing, recapturing the anguish Jeremiah and the other prophets cull from the heart of God, but instead we give you these words from Martin Sexton's "Where Did I Go Wrong?" [Maybe read them alongside the second chapter of Jeremiah in itself entirety, where God laments a lost love, saying "you were My lovely bride, you used to love Me? What happened? I gave you everything, but you left Me for another who treats you horribly. Why?"]

Where did I go wrong with you?

Where did I go wrong?

Was it something I said or did or didn't do?

Was all I had not enough for you?

All the life we were burning through

What with your memory shall I do?

I opened up the deepest of my inside

It was all I had left to give to you.

Where did I go wrong with you?

Perhaps ... no. No perhaps. God loves us and we act like unfaithful spouses.

And you probably think we're going to Hell for making this game, but you know we're right.

![O Come, O Come Emmanuel (Isaiah 7:14) [An Advent Card Talk]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55a9a1e3e4b069b20edab1b0/1483161046976-X5VJE3CMP9T957O72EII/3d-wallpapers-light-dark-wallpaper-35822.jpg)